How I learned I am white

Over the past couple years, several folks have given me professional opportunities that turn out — often quite a ways into discussion — to be premised on their belief that I am a person of color. This is how a rabbi taught me to respond.

My father was from northwestern India, my mother is a Pennsylvania-Dutch kind of American. That combination produced my older brother in 1971, then me in 1979. My brother is eight-and-a-half years older than I am, and he’s a little darker than I am. I get the sense people read my brother as nonwhite all the time, which was a liability in our southeastern Pennsylvania suburb in the ’80s. He did not have a good time in school.

I’m a little lighter than he is, and I went to the same schools nine years later. So while I got (relentlessly) pegged as queer, I never got told I wasn’t white. The handful of Indian kids in my school refused to believe I was Indian till they met my dad. (Indians still have a hard time believing I’m not adopted, so used to carry a family photo in my wallet.)

That’s how it is for me. Even now, I'm low-key aware of the fact that I get read as white in public, mostly because I’m super-duper aware that I might be read as queer. (Pretty much everybody in America does this kind of low-key social threat calculation, I imagine, though some might not know it.)

So. Over the past couple years, several folks have given me professional opportunities that turn out — often quite a ways into discussion — to be premised on their belief that I am a person of color. Those discussions got real awkward, real quickly, for everybody.

THEM … and it’ll be great to bring a diverse voice into this process!

ME (alarmed) Because I’m queer?

THEM Oh! Um well yes, that and …

ME That and what?

THEM (genuinely horrified) I mean! You are? A person of color so

ME No! Well, actually, um

It gets even more awkward after that. It turns out there is no conversational pattern to fall back on at such times. (We Americans, I think, do not have a very rich library of ways to talk politely about racialized identities.)

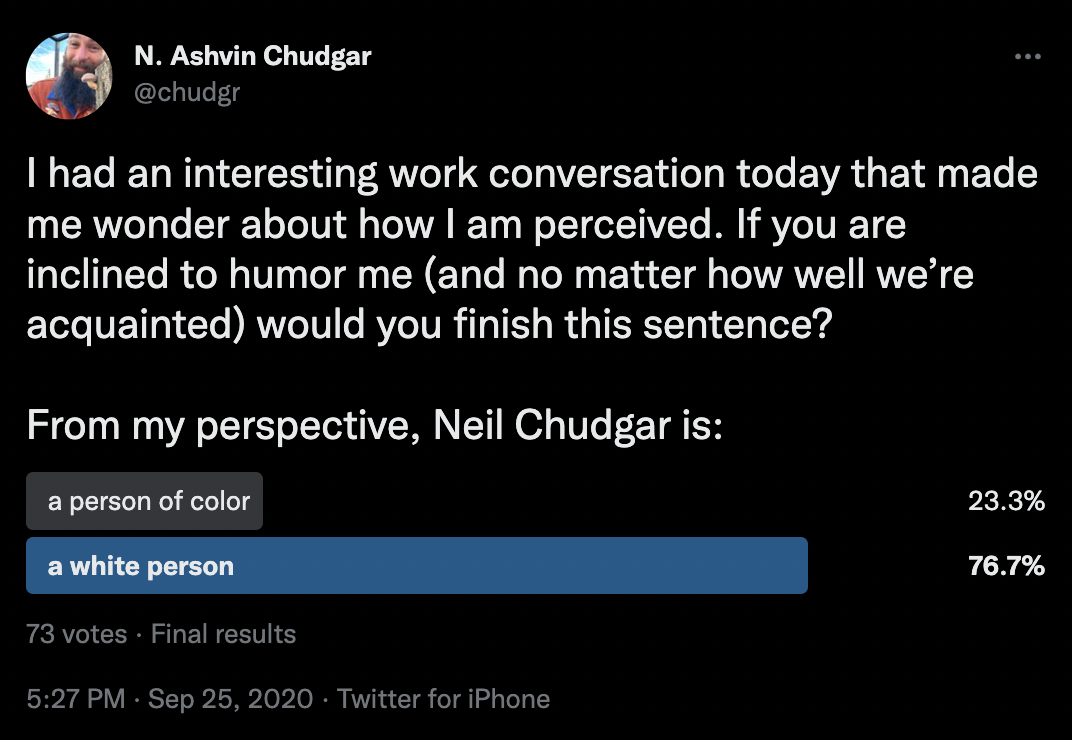

It was after one of those “Oh but I saw on your website that your father is Indian and I assumed” conversations that I ran this little poll:

Seventy-three people voted, which felt like a lot to me — but very few commented, perhaps because it wasn’t clear at all what I was after, and perhaps because it’s never clear what anybody is talking about when they talk about racial identity. A few friends said they knew I was a person of color because they know my history, but that if they didn’t, they’d see me as white. But that made me ask: Is there anything to whiteness other than passing?

Maybe not.

That settled it, I thought: three out of four Twitter poll-takers identify me as white; I move around the world as white'; but I'm half-Indian: ergo, I am “white-passing.” So I replied, when anyone asked, “My father is from India, but I pass as white.”

But then, months later, I read Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg’s reflection on whether Jewish folks are white. Here’s what she wrote:

It’s true that Jews were not coded as white in Europe, very much the opposite. And it’s also true that in the U.S., built as it is (literally) on antiblackness, I am seen as white and afforded the protection of whiteness in pretty much every aspect of my life. In stores, when I get health care, when I interact with the police, around my education and career, as a parent, etc. To deny that would be totally disingenuous as well as dismissive of the ways racism functions in American society. I’m white, and there’s no denying it. … We can only be allies in the fight against racism when we acknowledge this—the unfair advantages those of us with white skin are afforded as a result of that skin in a white-supremacist society. — Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg

“The unfair advantages those of us with white skin are afforded … in a white supremacist society.” This explains so much about my life: How my slightly-darker, much older brother had a dramatically different school experience from mine — and also why I’ve never felt entirely comfortable identifying as south Asian, since I know in my bones that people don’t think of me that way.

But this is the moment in the Rabbi’s thread that really hit home:

And to clarify, imho “white-passing” is a misnomer. It implies possibly getting away with something. When a doctor or cop or etc. finds out you’re a Jew, they continue treating you as white. Because: Whiteness has expanded to include Jews, has done so since the GI Bill.

— Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg (@TheRaDR) January 18, 2021

Exactly. Unless I happen to be around a bunch of people for whom race is really important — like the white nationalists we’ve all come to know all too well these past few years, and the people who explicitly want to hire consultants of color — people don’t change their behavior toward when they learn my father was from India. They don’t decide I am a different kind of person when they know where my father came from. My Indianness is a “fun fact” about me, like piano-playing or having cats. It does not expose me to harm or violence.

And that, this January 2021, is how I learned I’m not white-passing: I’m just white.

The consequences that follow from this understanding about myself are just starting to unfold. I don’t want to be white in America today — because to be white in America today is to be structurally harmful. Now it’s up to me to figure out the harms I’m perpetrating, and work to undo them.

Thanks to several good-hearted people in the nonprofit sector for enduring those intensely awkward are-you-or-aren’t-you conversations, to the Rabbi for her wisdom, and to the 73 people who took my Twitter poll.