My inner family and I spent last Saturday afternoon hanging out with hundreds of diverse conceptual people and their human-bodied spokesbeings. The joy I felt in that community inspired today’s newsletter: fun with grammar, including 3 easy ways you can give plural pronouns a try.

Here’s a fun language fact: English-speakers invented the singular they in the fourteenth century, when a vogue for stylish new indefinite pronouns referring to people of unspecified gender (like “everybody” or “no one”) created the need for a singular enby pronoun to refer to just one of them (“no one but them,” “everybody and their dog”). Alas, I did not know that a decade ago, when I was an obnoxious young English professor. Back then I compulsively “corrected” what I then saw as my students’ grammatical sloppiness. I must have crossed out they and scrawled “s/he!” above it a thousand times — even though I could faintly sense that the effort was not only futile but also kind of creepy.

To be clear, none of my students ever claimed they/them for themselves. By the time I quit professoring ten years ago, it still wasn’t customary to ask or offer pronouns, and I don’t think any student of mine ever told me theirs. Thank goodness they didn’t; I was so acutely uncomfortable with my own gender back then, I might have screamed or burst into flames if they had. But in the papers they wrote for my classes, my students used they as singular all the time — the way I’ve done three times in this paragraph already, just as ordinary users of English have been doing constantly since the early Renaissance.

I was literally a literary historian by training, but I never bothered to find that story out. Instead, I obstinately hewed to the joyless rigor of the Chicago Manual of Style, which (then and now) bans the singular they in academic writing.

Looking back on those years, I’m amazed by how tolerant my students were about my grammatical obsession. Though they gamely tried to purge their writing of singular theys, the sheer ordinariness of the word in actual English sentences defied my every attempt to eradicate it. By the time I finally washed out of academia, I’d come to admit that the word “they” will blithely continue to be as singular or as plural as it wants to be, ungendered and unbothered, seven centuries young.

The parts of me who managed my masculinity, with great effort, felt defeated and alarmed. Accepting the singular they seemed to put us on a slippery slope to something or other.

👨🏫 Fun with Grammar: Gender and Number

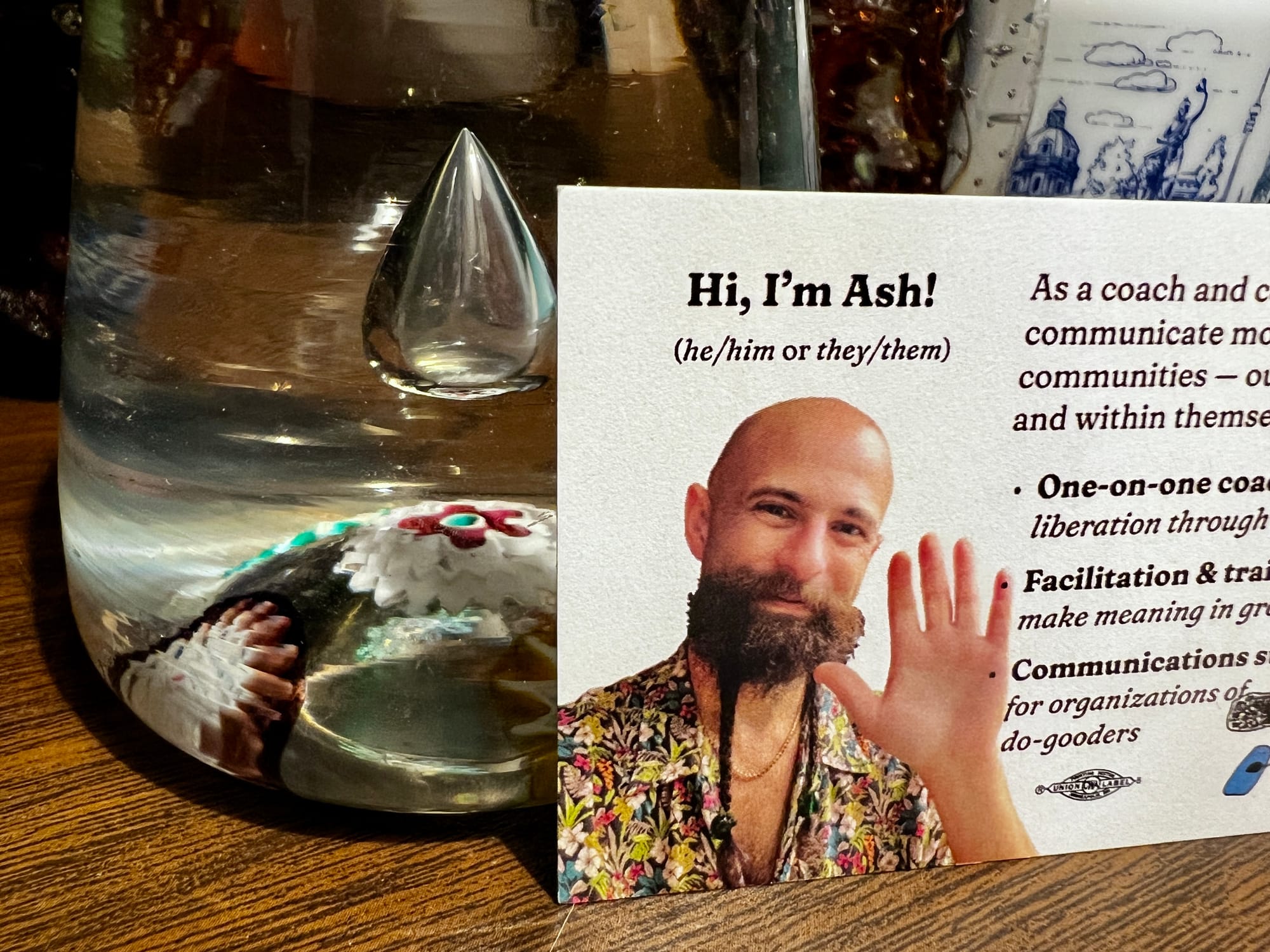

Slippery it was, and slip we did: a decade later, I go by he/him or they/them, and it says so right on my business cards.

Almost everybody I interact with defaults to he/him, what with my bald head and beard and so forth, which doesn’t bother me at all. These days I feel quite comfortable being a man in social interactions. But a marvelous few people do use they/them for me, and I secretly adore them for it. That tiny grammatical change makes otherwise ordinary workaday utterances (“Ash is going to walk us through their slides”) burst festively over my head like glittery little fireworks. Hearing myself referred to that way sometimes even makes me blush, as though “they” were a lavish compliment that, deep down, I had always hoped to receive.

Better yet, the word satisfies the compulsive urge for linguistic precision that bedeviled me as a professor. When applied to the human being known as Ash Chudgar, here and now, the word they is both idiomatically natural and rigorously grammatical in both gender and number.

Permit us to explain!

⚤ Gender: epicene

It is correct to call me them for because I am increasingly what grammar calls epicene and culture calls nonbinary.

I owe this startling development of middle age to the efforts of generations of queer elders and very lucky timing. My pokey progress toward wisdom and the grave intersected with history in such a way that my midlife existential crisis arrived just in time for an explosion of trans and nonbinary visibility around 2020. Lifelong ways of understanding my past and purpose were failing me; long-attached identities started coming unstuck, like sticky name-tags from woolen sweaters. At a time of Drag Race on TV and trans intellectuals on Twitter and queer radicals organizing everybody all over town, compulsory masculinity — an identity I’d always performed resentfully and awkwardly — got unstuck pretty quickly.

Today I am happy to report that my inner gender police force has been abolished, and all internal gender regulations not directly conducive to community safety have been repealed. This transformation, unexpected as it was, could not have succeeded without an internal truth-and-reconciliation process of sorts, whereby my former inner gender-cops and those they oppressed got to hear each other’s stories. Having taken public accountability for the harms they’d done, the former cops took on new and better jobs — bodyguard, doting grandpa, drag mother-goddess, etc. Their new vocation, which they find deeply meaningful and rewarding, is to cherish and defend the gender-nonconforming parts of me they used to beat up and send to jail.

Meanwhile questions of gender expression, like most other day-to-day matters, are referred to an internal committee-of-the-whole. Every member of my internal family who wants to have an opinion gets to speak, and all significant non-emergency decisions are made by consensus. This deliberative process is how we decided to print he/they on our business cards, for example, and to soften the potential menace of our beard by braiding it with cheerful bobbles (seen above).

& Number: plural

It is also grammatically correct to call me them because I am increasingly what both grammar and culture call plural, as opposed to singular.

(Also as opposed to dual, about which more in the linkies below.) It would thus be quite right for my delightful colleague to say, for example, during a meeting, “Ash are going to walk us through their slides,” although that would not be very idiomatic. People would be like, “What?” But it would be, joyously, correct.

This way of understanding my identity has been slipping gently into the periphery of my awareness over the past few years, more a faint tinkle of bells or a subtle perfume than an explicit belief.

Then a conversation I had with a therapist friend a few weeks ago brought the grammar of who I am into my full awareness.

“I have been wanting to ask you,” Augustin said tactfully, “about the name of your newsletter.”

“‘A Year of Living Plurally’?”

“Yeah. So, ‘plural’ is a word with a pretty specific meaning for—”

“The plural community,” I nodded. Though I hadn’t really thought it through, my friend’s implied question made sense — and the answer felt pleasantly clear and easy. “I know; I’ve been reading a lot about plural folks. It’s — aspirational, I guess? It just feels increasingly … accurate. If that makes sense.”

“I was just curious,” he said, grinning. “And I figured.”

It was that conversation, I think, that made me impulse-buy a ticket to the webinar I attended last Saturday — among the most healing and liberating surprises of this Year of Living Plurally so far.

🎉 The Joyful Community of Communities

Last week’s event was convened by Stronghold, the charismatic Dutch system who founded The Plural Association. They turned out to be much gentler and warmer in real life than their powerful, no-nonsense writing had led me to expect. They were convening the global community of plural people for a celebration to mark Dissociative Identity Disorder Awareness Day (March 5), an annual gathering Stronghold described as “the most anticipated event of the year for Systems!”

A cynical teenage part of me rolled his eyes at that bit of copy on the website. I mean, how much can you really look forward to a two-hour Zoom about a mental-health diagnosis?

A whole lot, as it turns out!

There were two presentations, not only wildly informative but also deeply moving, by eminent plural systems — a distinguished clinician and a beloved community advocate. Both spoke with courage and candor about the complexities of their own inner communities. We had a lively Q&A with them and Stronghold afterward.

But honestly, the content of the webinar was almost beside the point. Even on the internet, where all of us and our inner multitudes could only interact by way of a slender chatbox and little flurries of emoji, the warmth of solidarity with wildly various strangers was palpable. It’s a feeling I remember vividly from my years of sobriety. Waking into an A.A. meeting, any meeting, anywhere — different faces, different church basement, same weak coffee and steadfast fellowship among kindred weirdos, trudging the road together.

In the chat, as systems from all over the world shared our stories of struggle and swapped scars and lore, our pronouns flickered like cheerful candle-flames between “I” and “we.” We asked each other plural questions we couldn’t ask our spouses or therapists or friends, and got answers. Does anyone else have a little one who just cries all night? Of course we did, and we had childcare tips. What do you do with a headmate who wants to kill your body? Sympathetic chuckles and practical advice arrived promptly with a flurry of hard-earned 😂s and warm ❤️s.

Many of the systems on the call came with the diagnostic label of of Dissociative Identity Disorder (colloquially “DID,” pronounced did) stuck to the outside of their human bodies, tightly or loosely. It was under the banner of that malady, after all, that Stronghold summoned us all. Many of us came stickered up with other DSM letters, too — lots of PTSD, CPTSD, and OCD (all of which I have worn on my tweedy lapel), and above all the dreaded BPD (which I only escaped, I think, because I am not female). But few beings in attendance seemed to find these psychiatric stickums particularly binding or authoritative.

Among my fellow plural systems, I gathered, such categories are understood to be kludgy workarounds that, in the best cases, enable certain kinds of external support and internal self-understanding — but more often result in self-hatred from within and oppression from without. It is one thing to claim a plural identity in comfortable middle age, as my inner family and I have done, after discovering your own multiplicity on the way to healing and liberation. It is far more common to have your multiplicity diagnosed as a terrifying symptom of a sinister spiritual or psychiatric disorder and treated accordingly — or to have your very experience of consciousness written off as a fantasy, a delusion, or a lie. (Many thanks to my friend Forrest and their inner world for helping me think this through.)

The other systems I encountered on Saturday brought the same scientific skepticism to the myriad therapeutic strategies mental-health practitioners have devised to reckon with internal multiplicity — including Internal Family Systems, the model that introduced me to my own system. There are many others, from EMDR to PIT to TIST. (So many letters!) We talked about how we’ve tried them out, put them through their paces, and taken what works while leaving the rest.

Saturday’s joyful community of communities taught me something very important. No theoretical model, no matter how elaborate, can possibly encompass the sublimely opulent diversity of life in human beings’ inner worlds. And, even better: no theoretical model can capture the sheer joy of being a we among uses. No matter how frustrating or infuriating or downright scary the sundry inhabitants of our consciousness may be, their company is the one thing we can be sure of, always and forever.

When you’re plural — when you know and feel yourself to be not just I but also we — you can always say, no matter what external others may believe, with grammatical rigor and (eventually) even joy:

If there’s even a little inkling of multiplicity in you, dear reader, I think you get what we’re saying here. You and your whole family are invited to next year’s gathering.

But if you all this seems too good, or too weird, to be true — if you feel like you’re just the one person, a single consciousness without any internal complexity — then we invite you to try on plural pronouns for size, just as an experiment.

Three Easy Ways to Enjoy Being Yourselves

1. 🏟️ Root for Your Team

Although it’s still considered exotic to refer to yourself as “we/us,” larger forms of plural identity are common and widely celebrated. If you’ve never experienced yourself as plural before, this is an easy way to try multiplicity out. Try saying “we” along with the community you identify with most joyfully — for example,

- all the fans of our team,

- all the stans of our icon,

- all the partisans of our ideals,

- all the members in good standing of our club,

- all the fellow travelers on our chosen path,

- et cetera.

Say, “We are the best!” Say, “Never count us out!” Say, “Yes we can!” This kind of chosen big belonging — fellowship, fandom, esprit de corps — is the easiest, most frictionless way I know for a person to move from the lonesome isolation of I/me to the joyful plurality of we/us.

If you find yourself struggling to identify this kind of us, imagine them — those you are opposed to on a visceral level. For example, your us might emerge from your rage at those who would deny your bodily autonomy, or your inchoate loathing of the Dallas Cowboys. (Now, if the the us you discover in this way makes you uncomfortable, take heart: you can always pick a different us to belong to.)

2. 👪 Celebrate Your Entourage

Now move a little inward, from the kinds of us you’re part of with otherwise-strangers to the we you are with the beings you live most of your life with — those the absurd French language, adorably, calls your entourage. So try saying “we” in a way that includes those who are close to you, who might include:

- the couple you are with your partner or spouse,

- any family members you’ve ended up sharing your life with,

- whatever non-human animals you have chosen to take care of,

- the ancestors who still show up for you,

- and so forth.

So say, for example, “We enjoy video games.” Say, “Our house is your house.” Say “Get off our lawn.” Say whatever is true of the us you find yourself sharing your life with, here and now. This is a practical, day-to-day way to be more than just I/me. Using plural pronouns in this way will help you show up more comfortably in your relationships, even if they are very troublesome.

3. 🎤 Speak for More of Yourself

Moving even farther inward, you can try out plural pronouns all by yourself, simply by taking your ordinary mental dialogue seriously and literally. This is a handy trick to practice any time you’re feeling beside yourself — undecided, torn, conflicted, irrational, or crazy.

Such common human states of mind are much less unpleasant from a first-person plural point of view, believe it or not. Try it and see! This doesn’t require any outward action, or even any particular effort of imagination. Just saying the words in your head will do the trick nicely. For example:

- When a nasty inner critic whispers, “Ugh, you’re disgusting,” take a breath before you react. Imagine that critical voice is a part of you — not all of you, for sure, but somebody inside you, with a perspective that should count. And together, you and this part of you are constitute an us. So you can say, in your head: “We are feeling disgusted at the moment.” And just like that, the critical part of you knows they’re not alone: they’re part of the we that you brought them into just by saying those words in your head. Magic!

- When a frightened inner child throws a tantrum in your belly, don’t kick it out of consciousness for being such a stupid baby. Instead, include that inner child’s experience: say, “We’re a little bit frightened right now.” And just like that, the little one inside of you has you for company, so things don’t feel so scary.

Including various parts of yourself in the we of your inner dialogue is magic. But again, don’t take my word for it — try plural pronouns out for yourselves.

That’s all for this week, friends — write back for any reason, or none at all.

🔗 Linkies

🔠 So many freaking letters

Here is a handy glossary of all those mental-health initialisms:

- DSM refers to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a stunningly popular compendium of monetizable fantasies about madness now in its fifth (!) edition. If you are an American human being, this is the book that tells the healthcare system how to parse your spiritual and psychological wellbeing. Read it with, um, caution.

- PTSD refers to post-traumatic stress disorder, a condition of persistent horror initially described among survivors of the First World War as “shell shock.” The DSM has included PTSD as a diagnosis — that is to say, a medical condition that clinicians are allowed to get paid to treat you for — since 1986, after the condition was widely recognized among American soldiers who had survived their deployment as weapons of war in Vietnam.

- CPTSD is complex post-traumatic stress disorder, first described by the great psychiatrist Judith Lewis Herman in 1992: “The syndrome that follows upon prolonged, repeated trauma needs its own name. I propose to call it ‘complex post-traumatic stress disorder.’” Herman derived this description from years of treating the extraordinary suffering of ordinary women, from which she concluded that “the most common post-traumatic disorders are not those of men in war but of women in civilian life.” I cannot recommend her book enough.

- OCD refers to “obsessive-compulsive disorder.” This is what a psychiatrist gave me fluoxetine for, and it fits my inner family rather well.

- BPD is an elaborate slander against traumatized women the psychiatrists who write the DSM refer to as a “disorder.”

- EMDR is “eye movement desensitization and reprocessing,” an interesting somatic form of psychotherapy that got popular in the aughts. It works by cuing your body to interact with your memories in different ways.

- PIT is Pia Mellody’s “post-induction therapy,” a 12-step-flavored account of internal multiplicity that I learned some things from.

- TIST is Janina Fisher’s “trauma-informed stabilization treatment,” a version of Internal Family Systems therapy my friend Forrest told me about. I really like Fisher’s concept of the “going-on-with-everyday-life self.”

✨ Grammar & glamor

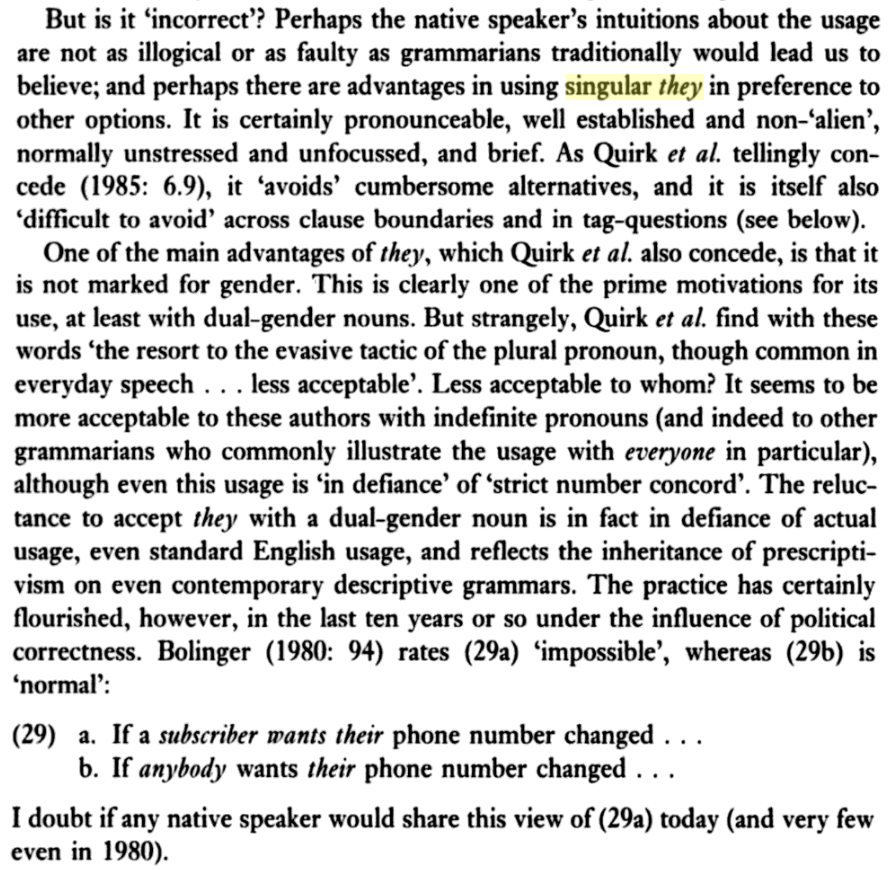

- The grammarian Katie Wales is a queer icon in waiting. Observe this sickening shade from her discussion of the singular they in Personal Pronouns in Present-Day English (Cambridge, 1996), darling:

- Meanwhile, The Oxford English Dictionary is here to school the bigots.

- The glamorous linguistic innovations of the fourteenth century apparently corresponded to a revolution in couture, apparently: “The draped garments and straight seams of previous centuries were replaced by curved seams and the beginnings of tailoring, which allowed clothing to more closely fit the human form.” That fancy tall medieval lady’s hat is called a “hennin,” it turns out.

🍒 The sexiest grammatical number

- Between the lonely singular and the sociable plural is the grammatical number called dual, which my Greek professor memorably explained as referring to “natural pairs, like balls.” This is the gnarly grammar work in words like “specs” and “either,” and the equally gnarly configuration of personhood that shows up in culture in such diverse forms as Dr. Jekyll / Mr. Hyde, Dr. Tobias Fünke / Mrs. Featherbottom, the Kevins / Mr. Vincent Adultman, and so forth.

- The community of plural systems, meanwhile, have collectively elaborated a rich taxonomy of dual ways of being.