When it’s your mission to solve problems that haven’t yet been solved, you have to help other people imagine a better world that doesn’t yet exist. To do that, social justice communicators can learn to use the powerful conceptual tools of science fiction and fantasy. Here’s a workshop about how.

This workshop, originally created for St. Olaf College’s Social Impact Scholars program, was presented in this form at a Minnesota Association of Nonprofits spotlight series on August 7, 2025. The slides are below, and a written-out version of the talk follows.

Nonprofits and new worlds

I want to start with a simple fact: Nonprofits (and other organizations of do-gooders) only come into being because the real world is broken. People recognize that the world, as it is now, isn’t set up to make a good thing happen that they care deeply about. So they set up an organization to fix the world in such a way that the good thing they care about can and will happen.

(By the way: all that follows applies not just to nonprofits, but to movement organizations, electoral campaigns, mutual-aid groups, and so forth — any society of people who come together to make the world different and better. I’ll just talk about “nonprofits” for simplicity.)

You could say that, when they organize to make something good happen, people are simply modifying the real world. But I think they are also doing something much more profound: By creating the conditions under which something impossible becomes possible, nonprofits are building a new world.

Here’s how I think of it schematically, where X is any good thing:

In the real world,

- Problem: Although X would be great, it’s just not happening

- Solution: None; that’s how things are.

By refusing to accept this state of affairs, the people who organize to pursue X are effectively creating a whole new world — one that’s identical to the real world, with one crucial difference.

In Nonprofitland,

- Problem: Reality is simply unacceptable unless X is possible.

- Solution: We organize people, systems, and energy to make X happen.

Problems and solutions exist in a world. Nonprofits have to build the world where the good thing they want to have happen is both necessary and possible, so they can organize other people, systems, and energy to achieve it.

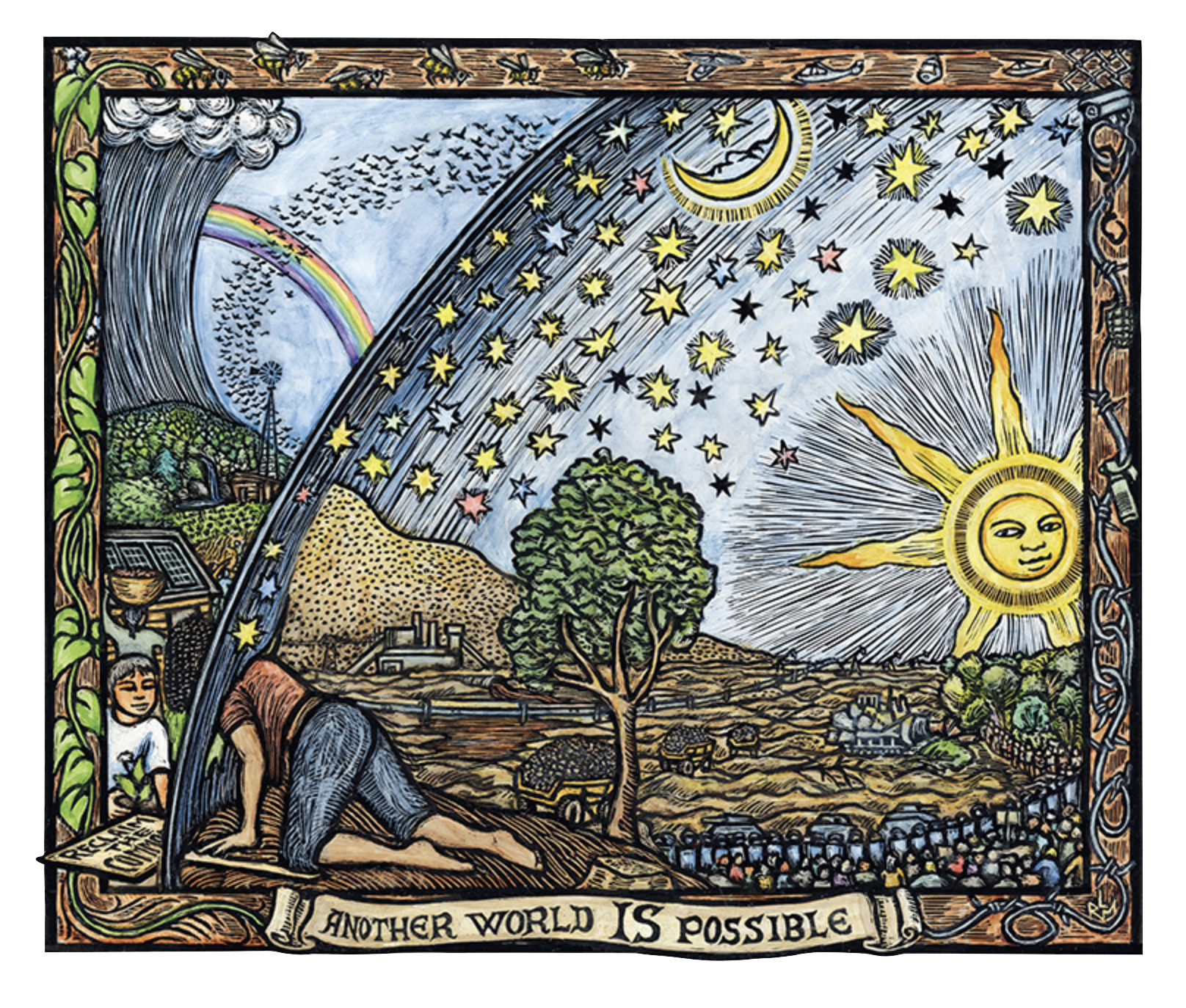

“Another World Is Possible”

Framing what nonprofits do as “worldbuilding” might seem like a fanciful metaphor, but I think it’s just a restatement of a familiar leftist maxim: “Another World Is Possible.” Here’s a beautiful illustration of that idea by Minneapolis’s own Ricardo Levins Morales:

Nonprofits begin from this belief — which sets up a tricky challenge for communicating. How do you convince people that things don’t have to be the way they are? That, in essence, is the problem of nonprofit communications.

As the great prison abolitionist organizer Mariame Kaba puts it in We Do This ’Til We Free Us (2021),

“Our charge is to make liberation under oppression completely thinkable.”

Making good things (like liberation) thinkable — under conditions (like oppression) designed to make make them unthinkable: that is what makes progress possible. The end of slavery in the U.S. was unthinkable until abolitionists made it thinkable. The right to vote for women was unthinkable until suffragists made it thinkable.

And to make something thinkable, you need a world to think it in. That’s because, to quote a pioneer in public-opinion polling,

The way in which the world is imagined determines … what people will do.

Walter Lippmann said that in 1929 — a time very much like ours, with soaring inequality and deep social conflict. He’s cited here by the quoted by FrameWorks Institute — an excellent resource for people who have to communicate about social issues. They call the discipline of world-imagining “framing.” But I’d encourage you to call it what it is. “Framing” in issue means building a world in which the problems the real world accepts as inevitable can and will be solved. “Framing” is building the world you long to live in.

Worldbuilding in fiction

Fiction shows how purpose-built worlds can reimagine real-world problems in transformative ways. For example, in the real world:

- Problem: Climate change is rapidly making life worse for humans.

- Solution: ¯\(ツ)/¯

You don’t need me to tell you that none of the solutions currently on offer is remotely adequate to the crisis. In the world we live in now, the problem of climate change is effectively unsolvable.

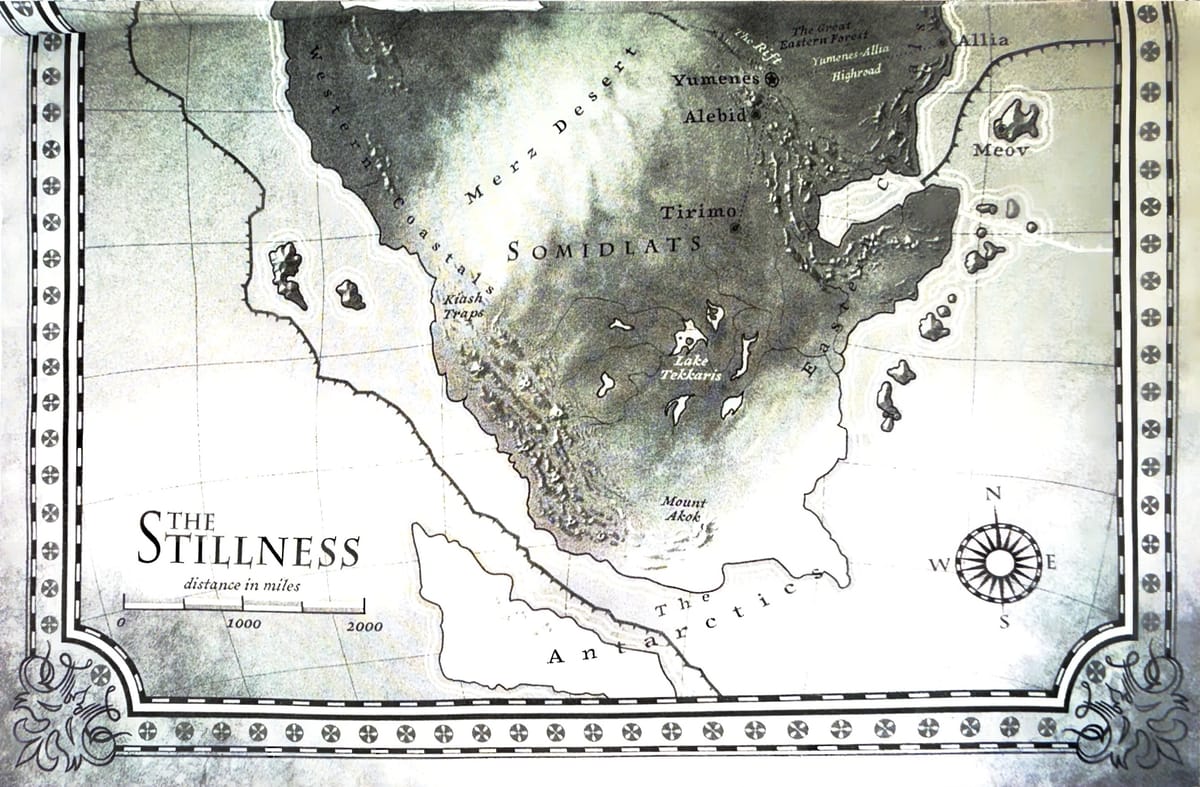

In the world of N.K. Jemisin’s brilliant Broken Earth trilogy (2018), the problem is very similar, but reconfigured in a way that allows for a dramatically different solution. In this world,

- Problem: The earth is punishing humanity for having hurt him

- Solution: Humanity reorganizes to avoid making the earth angrier

In the world that Jemisin imagines, it is commonly understood that previous generations of human beings antagonized Father Earth so grievously through their extractive practices that the planet himself began producing catastrophic geologic and environmental events in order to punish them. So humans have spent many generations re-learning how to live on the planet in ways that aren’t extractive, in the hope that Earth will stop punishing them with catastrophic weather. The world of small-scale human communities that Jemisin builds lets us imagine, in vivid detail, what it might be like to live in a post-extraction future — and where the very has the moral dignity of personhood. It reconfigures the problem to make a solution thinkable.

Sometimes, fictional worlds can help us by heightening a real-world problem in a way that helps us understand it more vividly. In the summer of 2022, when I first gave this workshop, the Supreme Court had just confronted the real-world U.S.A. with the very same problem that plagues Gilead (1984):

- Problem: The law forces people to give birth against their will

It was no accident that our national reality so closely resembled Margaret Atwood’s fictional world; in building it, she resolved not to “include anything that human begins had not already done … or for which the technology did not already exist.” And people in both worlds have come to the same conclusion:

- Solution: Oppressed people organize rescues & resistance

As in Gilead, so right here and now.

Handy worldbuilding techniques

So: fictional worlds can transform how we communicate about the real world by reimagining unsolvable real-world problems in such that they can be solved.

Here’s a nifty example, from the world of Battlestar Galactica:

- Problem: Human beings mistreat other beings because they think they’re the only species that matters.

- Solution: Nonhumans indistinguishable from humans vigorously argue this point, arriving finally at something like mutual respect.

Here’s another one at a smaller scale, suggested by a workshop participant yesterday:

- Problem: Students with unusual learning needs don’t get appropriate education

- Solution: Identify, notify, and transport such students to free schools, created just for them

That’s Hogwarts, of course. The United Federation of Planets comes up frequently in workshops, too:

- Problem: Inequality runs rampant despite abundance

- Solution: Representative democracy redistributes resources equitably and abolishes money

Fictional worlds, as various as they are, reconfigure real-world problems in some common ways:

- Defamiliarize the problem, so people can see it in a new way. (Non-human creatures are great for this purpose: consider Zootopia.)

- Deepening the sorrow, so you can feel the problem more intensely. (Fiction lets you do this using point of view, as famously in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.)

- Make the problem literal, so the world itself expresses the problem. (In The Silo, for example, exploited workers live physically underneath the professional-managerial class.)

Fictional worlds allow for reimagined solutions, too:

- Make the solution familiar, by describing it in vivid detail, or repeating it. (Often the structure of a quest or journey will help here.)

- Heighten the triumph so you can feel the joy and happiness of the solution. (I think of the scene at the end of Star Wars.)

- Make the solution mythic, so solving the problem is not just a matter of policy, but a matter of sacredness or bringing order to the universe. (The Narnia books are a great example of this, although the “problem” C.S. Lewis seems to be solving is modernity per se, which—?)

Worldbuilding in Minnesota

A world where all families are free

Back in 2012, there was a problem that many Minnesotans wanted to solve:

- Problem: Same-sex couples in Minnesota cannot marry

The common-sense solution seemed to be to persuade voters to be more tolerant of sexual minorities. But that didn’t work, since Minnesotan straight people showed very little inclination to “tolerate” queer people.

So the geniuses at “Minnesotans United for All Families,” the nonprofit PAC that was campaigning for marriage equality, imagined a different world where the problem was entirely different:

- Problem: Some Minnesotan families are unfairly denied freedom.

This is a completely different way to think about the problem. And once you’ve framed the problem that way, a new solution presents itself:

- Solution: Persuade voters to defend freedom for all Minnesota families

The orange-and-blue lawn signs were everywhere: “Vote No: Don’t Limit the Freedom to Marry.” That year, Minnesotans voted by a 110,000-vote margin to legalize same-sex marriage, and I myself am married to another man (for now)!

How did Minnesotans United rebuild a world around a new problem and solution? What are the advantages of the new world they built? Any potential disadvantages?

A world where everyone is safe

Worldbuilding is hard: sometimes, the real world just isn’t ready to imagine that things can and should be different.

Again in Minnesota, eight years later, the Minneapolis Police Department made the whole world focus on a very long-standing problem:

- Problem: Police officers hurt and kill Black people with impunity

- Solution: Stop police officers from hurting and killing Black people

I bet you remember what that moment felt like — the problem was so vivid, so real, so horrifying, that it felt as though things had to change. Reality was clearly, obviously broken; another world had to be possible. At the time, huge majorities of Americans seemed to agree. The solution to the problem was clear — a solution that prison and police abolitionists had been proposing for decades: Defund the police.

Here in Minneapolis, an amazing coalition of organizers advocated for a ballot measure to amend the Minneapolis charter to replace the MPD with a Department of Public Safety. Led by the brilliant JaNaé Bates, the Yes 4 Minneapolis movement framed the solution the problem of police violence in a more positive way: “Expand Public Safety.” Minister Bates and her team wanted us to imagine a new world where there was more safety, safety for everybody.

I am very sorry to say that, despite truly heroic mid-pandemic organizing efforts, Minneapolis voters rejected that ballot measure by 12 points. Today, four years later, the Minneapolis Police Department has more funding than ever before; and nationwide, police officers killed more Americans in 2024 than in any year on record.

Now you try

If you are in the business of nonprofit communication, the organization you work for has already brought a new world into being: a world in which the problem you want to solve is so intolerable that reality itself must change to make solutions possible.

Thinking that way, you can transform how you think about your messages by building new worlds on purpose. And to do that, you can use the powerful tools of fiction. In the new world you build,

- You can make the problem you care about helpfully unfamiliar, and you make the solution feel familiar.

- You can deepen the sorrow of the problem, and heighten the glory of solving it.

- You can make the problem concretely literal in some way, and make the solution noble and mythic.

So go forth, communicator, and build new worlds. You cannot build too many. The rest of us need them all.